Published: 10/09/18, Last updated: 6/06/23

Introduction

(last updated 9/9/20).

Despite slightly declining beef consumption rates in this country, beef is still what’s for dinner in many American households. Most consumers think of it merely as a delicious meal, turning a blind eye to the process that makes those burgers ubiquitous on restaurant menus, backyard grills and dinner tables.

But, overall, global beef production has a dangerously large foodprint: most beef production is resource-intensive and extracts a huge toll on the environment. These intensively raised cattle are kept in crowded, unhygienic feedlots and fed an unnatural diet. They produce toxic amounts of methane gas, making them a prime contributor to global warming. They’re slaughtered at speeds that are too fast to ensure safety for workers or to prevent feces from contaminating their meat. This system is bad for cattle, devastating for our environment, dangerous for the workers who process them and unhealthy for the humans who eat the meat.

There is an alternative. There are models in this country for what sustainable beef production can look like: ones that are better for the animals, for workers, for local communities and for the environment.

What Beef Should Be

- From cattle raised in clean and healthy conditions, primarily grazing on pasture.

- From cattle raised without hormones or other drugs (using antibiotics only to treat sick animals).

- From cattle allowed to display natural behaviors.

- From cattle raised by independent farmers who have fair access to processing, distribution and retail markets.

- Produced with the least possible negative impact on the environment.

- From animals on well-managed, biodiverse, pasture-based systems and fed a forage-based diet.

- From animals transported and slaughtered humanely, including pre-slaughter stunning.

- Transported and slaughtered humanely with minimal stress and suffering, and in facilities that pay the utmost attention to animal health and welfare.

- Butchered and handled carefully and safely.

- Processed by well-trained workers making a livable wage, working at safe speeds and without injury.

- Tasty and nutritious.

Unfortunately, most of the beef on the US market meets none of these criteria. This is bad for people, the animals, local communities and the planet.

The Beef Industry is Powerful

Inhumane Practices

Hot prods or electric shocks are commonly used to move cattle, and while more humane methods of transport have been developed, the crowding, noise and sudden movements can still cause stress for the animals. 9 (See Worker Health and Safety for more on line speeds.)

Cattle Feed

Cattle are ruminants and graze on grass and other forages (plants that grow alongside grasses). However, no grass grows in feedlots — in fact, part of the definition of a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) is that animal traffic is so intense that grass does not grow.

The diet of feedlot cattle primarily consists of grains; generally, a mix of corn with soybeans for protein. Their diets can also include:

- Byproducts or excesses from other parts of the food system, such as candy, orange pulp from juice factories, cookie crumbs and other bakery waste, beet tops from sugar production or spent distillers’ grain.

- Animal byproducts, including poultry litter and animal waste. 14

Animal Health Equals Human Health

Americans consume about one pound of beef per week – three times more than the recommended portion (of two to three ounces of red meat served once or twice a week). When it comes to what animals eat: what’s good for animals is good for people. Grain feeding limits animals’ ability to create certain kinds of conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs), considered “good” fatty acids, specifically omega-3 fatty acids, which have many human health benefits, including reduced cancer and cardiovascular disease risks. (A CLA ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids between 1:1 and 4:1 is considered ideal.)

Grassfed beef typically is high in omega-3 fatty acids, while grain-fed beef has almost none (both have similar omega-6 profiles). 16

Environmental and Community Impacts of Beef Production

Industrial beef production is highly resource-intensive. Inputs into the system are excessive and highly concentrated — and so is what results.

Too Much Manure

One of the most negative aspects of industrial beef and other animal production is excessive amounts of manure.

Manure can be a rich source of soil nutrients. When applied in appropriate amounts, manure returns nitrogen and phosphorous to the soil, enriching farmland, pastures and grassland. Industrial animal farms can produce between 2,800 tons and 1.6 million tons of animal waste a year. 24

The science is still evolving, but we know:

- That pasture health is correlated to the soil’s capacity to trap, or sequester, carbon, which is a good thing. 28

Progressive farmers around the world are studying pasture-based systems closely as an opportunity to reduce the climate impact of beef production. Soil is alive. When nurtured in a pasture-based system (without chemicals or drugs), healthy soil can absorb a great deal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and be an extremely efficient “carbon sink” that can also process manure directly on site and into the soil. The better and more diverse the pasture and the deeper the root structure, the more carbon it can sequester. Alternative cattle breeds are also an important element of the system. Animals bred for feedlot production are not necessarily the best at optimizing energy conversion from grass in a pasture-based system.

These types of regenerative practices explore new frontiers, beginning with improving soil health (not just maintaining it), which helps the environment all the way up the food production chain. Some of the methods currently being implemented will define the best beef farming practices of the future — not only for reducing and capturing greenhouse gas emissions, but to get animals to their finishing weight quickly without compromising the health of the entire system.

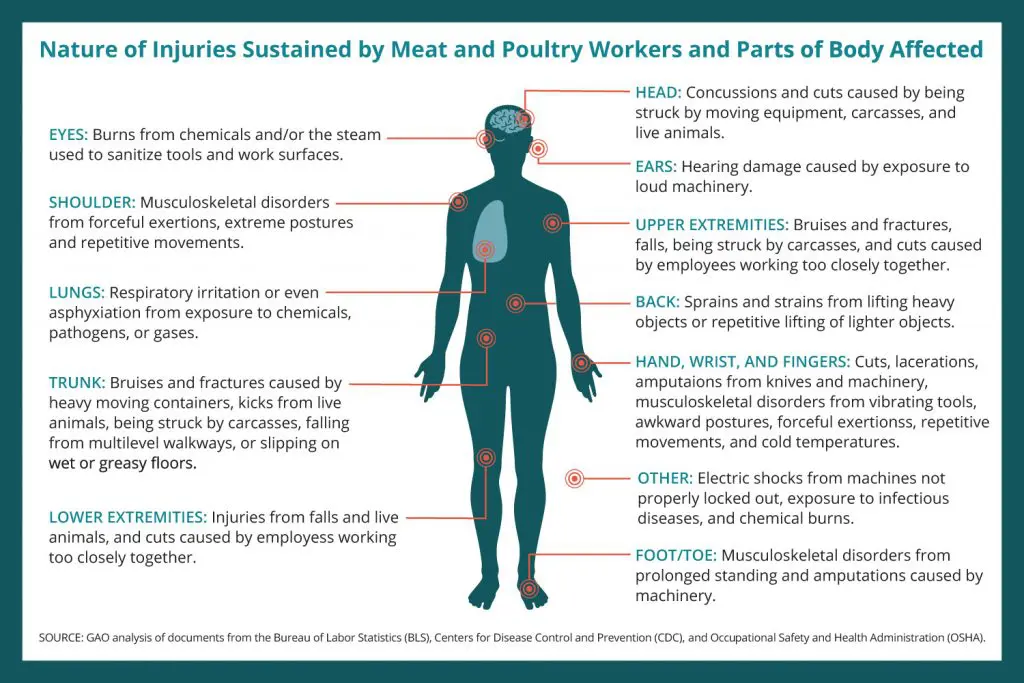

Worker Health and Safety

It is not only the animals who suffer in the industrial feedlot system — workers on farms/feedlots and in processing plants do, too. But what happens when workers try to change that system? Whistleblowers are often harassed into stopping their complaints, or are outright fired, with little legal recourse.

Here are some of the ways that worker health and safety are compromised in industrial beef production:

On the Farm

Working with cattle is physically demanding and can be dangerous. According to the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, in 2011, injury rates for workers in animal agriculture were 6.7 per 100 workers, compared to an average rate of 3.8 injuries per 100 for all workers. 36 CDC estimates suggest that 22 percent of these illnesses and 29 percent of foodborne illness deaths are attributable to beef. 37

Between 1998 and 2008, beef accounted for:

- 99,000 illnesses from Salmonella and coli.

- Nearly 2,400 hospitalizations.

- Thirty-five deaths.

- $356 million estimated health care costs. 41

Salmonella bacteria are the most common cause of foodborne illness across all foods; Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Clostridium perfringens and Enterococci are some of the other illness-causing pathogens found in beef. The US Department of Agriculture requires testing only for Salmonella and a specific strain of especially dangerous E.coli.

Antibiotic Overuse and Antibiotic Resistance: A Public Health Crisis

An even more alarming danger being bred in feedlot beef cattle is antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Antibiotics have been used in livestock feed since the 1940s, when studies showed that the drugs caused animals to grow more quickly. 54

Of additional concern, in Consumer Reports’ 2015 findings, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), an increasingly common strain of bacteria resistant to many antibiotics, was found in three samples of conventional beef. MRSA was not found in the more sustainably-raised beef Consumer Reports tested. 56

Other Drugs and Additives in Meat

Drugs, including growth hormones, are regularly given to cattle in feedlots to make them gain weight more quickly on less feed. Some of these drugs, like the growth-promoter ractopamine, have been banned in many other countries.

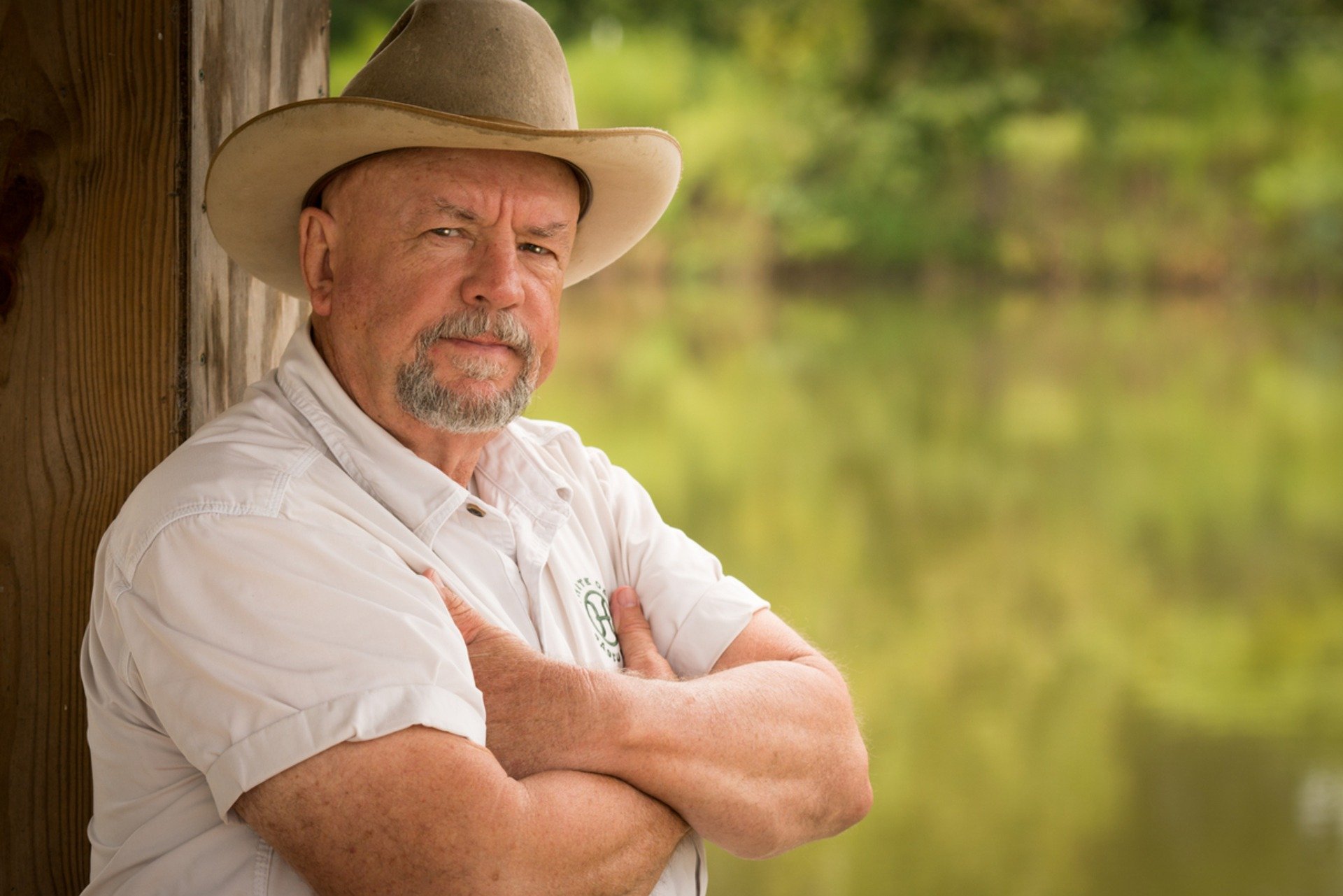

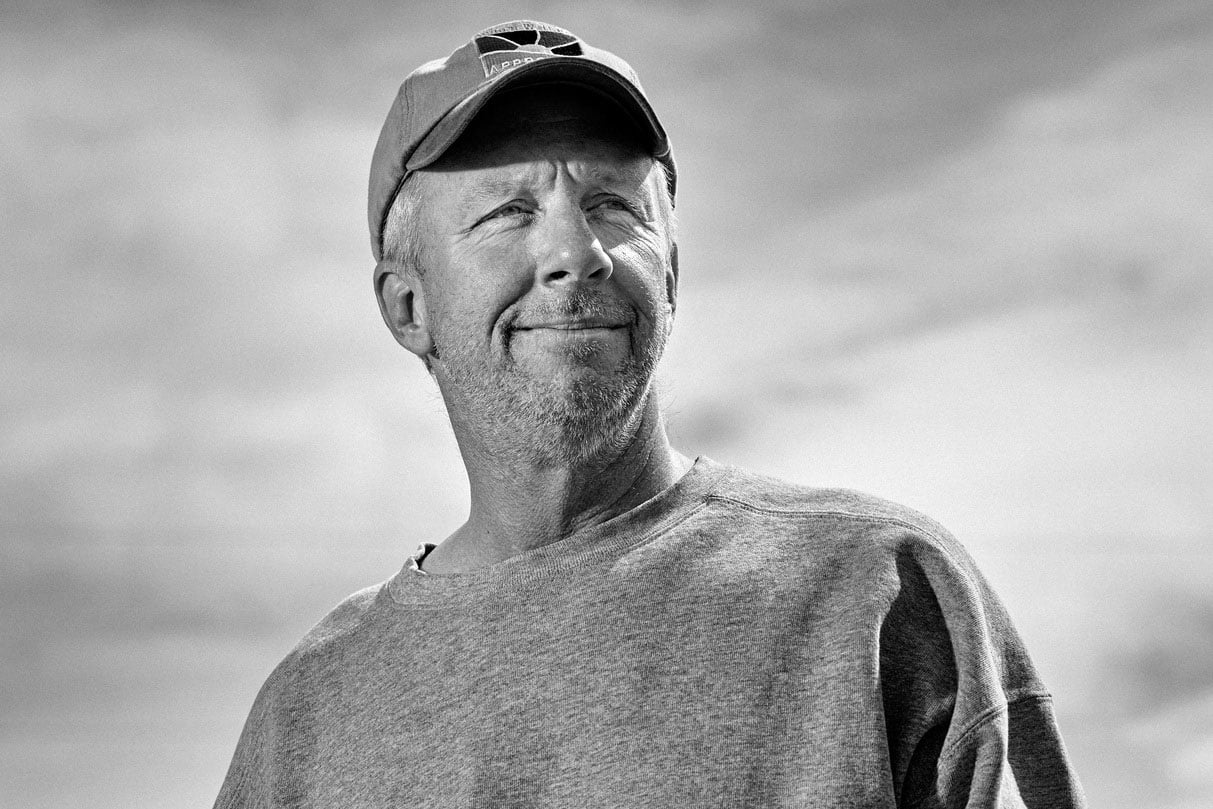

Until we have better regulations that change the way most of our beef and other meat is produced, the ability to shift demand is in the hands of those who are buying: consumers, institutions, retail outlets, schools, hospitals and more. Collectively, we can shift demand. Here’s how: There are many reasons to decrease how much beef you eat. If nothing else, beef is a resource-intensive, inefficient food: only one percent of gross cattle feed calories is converted into calories humans can eat, and only four percent of the protein cattle eat becomes protein humans can eat. Consuming less beef overall can also mean spending your beef dollars on more sustainably produced, better quality meat, instead. To put a more positive spin on it: the less beef that needs to be raised, the better that beef can be — meaning fewer environmental impacts with healthier results for animals and people. Sound daunting to eat less beef? Here are some ways to get started: Beef labels are complicated. There is no one label that comprehensively accounts for if the cow was raised entirely on pasture, if that pasture was sustainably maintained, if the animal was well treated and if the workers were fairly treated and compensated. As a result, consumers must decide what factors are most important to them and then seek out the appropriate label. The most comprehensively useful labels you can find are the Certified Grassfed by a Greener World (AGW) (an optional, additional accreditation to Certified Animal Welfare Approved by AGW), the PCO Certified Organic Grassfed label and the NOFA Certified Grassfed label since they require that the animals ate a pasture-based diet of only grass, were never confined to feedlots, and had no daily diet of drugs. The certified Animal Welfare Approved by AGW label (without “Grassfed”) is also very meaningful when it comes to animal welfare standards, including comprehensive standards for raising, transport and slaughter. The USDA Organic label has among the strongest standards for environmental sustainability, including prohibiting synthetic fertilizers and industrial pesticides, as well as stringent standards for 100 percent Organic feed. The Certified Naturally Grown label, started by farmers who did not want to go through the organic certification process, has similarly high sustainability standards, but does not include third party certification, as with USDA Organic or the Animal Welfare Approved by AGW labels. Higher than both of them is the Biodynamic label which would be our very top pick if it were more widely available. Though it is not widely available, the Food Justice certification is a comprehensive label for social justice in farming and requires farms to be certified organic as a prerequisite. To learn more about the many labels you might find on your beef, which ones are useful and which are less so, visit our Food Label Guide guide. Knowing what different cuts and grades of beef are will help you make the most of the meat you buy. While the USDA has established grading (“prime,” “choice” and “select”) for grain-finished beef, it has not established grading for grassfed beef. That’s in part because grassfed beef is leaner than grain-finished, so the fat marble grading system isn’t directly applicable. The best grassfed beef will come from animals that grazed as much as possible on diverse pasture. Look for “pasture raised” along with certified grassfed claims to buy the best quality grassfed meat. If you don’t know what the cut is, you won’t know how to cook it. Both an overcooked tenderloin and an undercooked chuck roast will be tough and less than tasty. This is especially true for leaner grassfed meat. A general rule is that the more active the part of the cattle the cut is from, the longer and slower it needs to cook. Cuts from the core of the animal — anything with “loin” in the name, along with cuts like hanger steaks and flatirons — are muscle mass that hasn’t had to work very much and is thus more naturally tender. These cuts can be cooked quickly. Cuts from the extremities, large joints and other load-bearing areas are tougher because they’ve worked more. Hip, shoulder, legs, neck — meat from these areas of the animal need to be slowly roasted or braised to allow the tougher connective tissue cook down and become tender. Despite the challenges, more and more farmers are raising beef using sustainable practices. Buying directly from producers — through community supported agriculture (CSAs) or at farmers’ markets — can be a good way to support those efforts and get amazing grassfed beef. Note also that many of the labels mentioned above have directories of certified farms and/or brands. Ethical consumerism — individual people making better choices when they purchase beef — is a great starting point, but working towards better regulations and practices industry-wide is also important. Will Harris raises cattle and other animals on land his great-grandfather started tending in 1866. After a life of raising cattle following post-World War II industry “best practices” that included pesticides, antibiotics and hormones, in the mid-1990s he started to realize that his ranch had become a monoculture. He ditched the chemicals and began working the land, much as his great-grandfather had, following sustainable practices that benefitted the soil, the animals, the people who worked the ranch and the people they fed. White Oak Pastures is now a model of sustainable farming in the US. Dan Gibson of Grazin’ Angus Acres Farm takes grassfed beef seriously. He’s spent years cultivating the most nutritious grass for his herd of 300 Black Angus cattle, a feed that he says results in beef with as much omega-3s as wild salmon. And rather than slaughter at the typical 12 to 15 months, Dan allows his cattle to graze for around three years, allowing for fully marbled, highly nutritious beef. These high standards have earned Gibson the seal of approval from third-party certifier Animal Welfare Approved, based on his care and concern for his animals and quality product. And at Grazin’, his Hudson, NY diner — the first Animal Welfare Approved restaurant in the world — you can taste that grassfed beef first hand and witness the synergy between restaurant and farm. While there are huge problems with the system by which most of the beef on the US market is produced, there are clear solutions at our fingertips. Some of those solutions are in the hands of farmers — like the ones we mention here. Some of these are in the hands of consumers — such as eating less industrially-produced meat and supporting the producers who are modeling better practices. Some solutions are in the hands of policymakers. Working together, we can foster a system of meat production, distribution and consumption that lowers beef’s foodprint. Change is on the horizon, and we all have a role to play in getting us there.1. Reduce Consumption

2. Look for Labels that Mean Something

3. Make the Most of What You Buy

Understanding the Grading System for Beef

Beef Cuts

4. Find Great Local Farmers and Ranchers

5. Work Towards Change Beyond Your Table

Meet Some Farmers Who Are Getting It Right

What Needs to Change

Conclusion

Hide References

- Mahanta, Siddhartha. “Big Beef.” Washington Monthly, January/February 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/janfeb-2014/big-beef/

- Ibid.

- Food and Water Watch. “Horizontal Consolidation and Buyer Power in the Beef Industry.” FWW, July 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/sites/default/files/beefconcentration.pdf

- Rack, Andrea. “How Safe Is Your Ground Beef?” Consumer Reports, December 21, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/food/how-safe-is-your-ground-beef

- Atkinson, Sophie. “Farm Animal Transport, Welfare and Meat Quality.” Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 2000. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/11026/1/Atkinson_S_140221.pdf

- Smith, T. “Feedlot animal welfare. 2010 International symposium on beef cattle welfare.” Retrieved from https://www.api-virtu-allibrary.com/isbcw-2010/isbcw_temple-grandin-feedlot-welfare.htm#.VWInAeuH0S1

- Code of Federal Regulations. “Title 9. Part 313. 9 CFR 313 – HUMANE SLAUGHTER OF LIVESTOCK.” Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/9/part-313

- Mader, TL. “Environmental stress in confined beef cattle.” Journal of Animal Science, 81(14): 110-119 (February 2003). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://academic.oup.com/jas/article-abstract/81/14_suppl_2/E110/4789865

- Food and Agriculture Organization. “Guidelines for slaughtering, meat cutting and further processing.” FAO, 1991. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.fao.org/docrep/004/T0279E/T0279E00.htm#TOC

- Code of Federal Regulations. “Title 21. Part 573. 21 CFR – FOOD ADDITIVES PERMITTED IN FEED AND DRINKING WATER OF ANIMALS.” Cornell Law Legal Information Institute, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/21/part-573

- Owens, Fred N. “Acidosis in Cattle: A Review.” Journal of Animal Science, 76: 275-286 (1998). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fred_Owens/publication/13765782_Acidosis_in_Cattle_A_Review/links/54ec9a2b0cf2465f532fbb6c.pdf

- Callaway, Todd R. “Diet, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Cattle: A Review After 10 Years.” Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 11: 67-80 (2009). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.horizonpress.com/cimb/abstracts/v11/67.html

- Global Development and Environment Institute and Tufts University. “Feeding the Factory Farm.” GDAE, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ase.tufts.edu/gdae/policy_research/BroilerGains.htm

- Ibid.

- Daley, Cynthia A et al. “A review of fatty acid profiles and antioxidant content in grass-fed and grain-fed beef.” Nutrition Journal, 9:10 (2010). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.nutritionj.com/content/9/1/10

- Animal Welfare Approved. “Beef Cattle and Calves Standards.” A Greener World, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://agreenerworld.org/certifications/animal-welfare-approved/standards/beef-cattle-and-calves-standards/

- US Government Accountability Office. “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations: EPA Needs More Information and a Clearly Defined Strategy to Protect Air and Water Quality from Pollutants of Concern.” GAO, September 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.gao.gov/assets/290/280229.pdf

- Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production. “Putting Meat on the Table: Industrial Farm Animal Production in America.” The Pew Charitable Trusts and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-a-livable-future/_pdf/news_events/PCIFAPSmry.pdf

- North Dakota State University. “Water Quality of Runoff From Beef Cattle Feedlots (WQ1667).” NDSU, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/environment-natural-resources/water-quality-of-runoff-from-beef-cattle-feedlots

- Fry et al. “Environmental health impacts of feeding crops to farmed fish.” Environmental International, 91: 201-214 (May 2016). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412016300587

- Mekonnen, MM and Hoekstra, AY. “The Green, Blue and Grey Water Footprint of Farm Animals and Animal Products. Volume 1: Main Report.” UNESCO-IHE, December 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://waterfootprint.org/media/downloads/Report-48-WaterFootprint-AnimalProducts-Vol1_1.pdf

- Water Footprint Calculator. “The Water Footprint of Beef: Industrial vs. Pasture-Raised.” GRACE Communications Foundation, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.watercalculator.org/water-use/water-in-your-food/water-footprint-beef-industrial-pasture/?bid=4712/the-water-footprint-of-beef-industrial-vs-pasture-raised

- Hribar, Carrie. “Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities.” CDC, (2010). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/docs/understanding_cafos_nalboh.pdf

- US Environmental Protection Agency. “Overview of Greenhouse Gases: Methane Emissions.” EPA, April 11, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases#methane

- Rodale Institute. “Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change: A Down-to-Earth Solution to Global Warming.” Rodale Institute, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://rodaleinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/rodale-white-paper.pdf

- Schnepf, Randy. “CRS Report for Congress. Energy Use in Agriculture: Background and Issues. Order Code RL32677.” Congressional Research Service, November 19, 2004. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://rodaleinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/rodale-white-paper.pdf

- Rodale Institute. “Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change: A Down-to-Earth Solution to Global Warming.” Rodale Institute, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://rodaleinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/rodale-white-paper.pdf

- Ibid.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. “NEWS RELEASE: Workplace Injuries and Illnesses – 2011.” US Department of Labor, October 25, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh_10252012.pdf

- Davis, Meghan F. et al. “Occurrence of Staphylococcus aureus in swine and swine workplace environments on industrial and antibiotic-free hog operations in North Carolina, USA: A One Health pilot study.” Environmental Research, 163: 88-96 (May 2018). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935117317383

- Mole, Beth. “MRSA: Farming up trouble.” Nature, July 24, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935117317383

- US Government Accountability Office. “WORKPLACE SAFETY AND HEALTH: Additional Data Needed to Address Continued Hazards in the Meat and Poultry Industry.” GAO, April 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676796.pdf

- Memo of Supreme Court Decision. “Wage and Hour Advisory Memorandum No. 2006-2.” US Department of Labor, May 31, 2006. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.dol.gov/whd/FieldBulletins/AdvisoryMemo2006_2.htm

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Cattle Inspection: Committee on Evaluation of USDA Streamlined Inspection System for Cattle (SIC-C). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235649/

- Ibid.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the United States.” US Department of Health & Human Services, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control. “Contribution of Different Food Commodities (Categories) to Estimated Domestically-Acquired Illnesses and Deaths, 1998-2008.” US Department of Health & Human Services, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/attribution-image.html#foodborne-illnesses

- Batz, Michael B. et al. “Ranking the Risks: The 10 Pathogen-Food Combinations with the Greatest Burden on Public Health.” University of Florida, Emerging Pathogens Institute, 2011. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://folio.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/10244/1022/72267report.pdf

- Ferdman, Roberto A. “I tried to figure out how many cows are in a single hamburger. It was really hard.” The Washignton Post, August 5, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from Https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/08/05/there-are-a-lot-more-cows-in-a-single-hamburger-than-you-realize/?utm_term=.08ab99a4dbda

- Consumer Reports. “Beef Report.” Consumer Reports, August 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/research/consumer-reports-beef-report/

- Heiman, Katherine et al. “Escherichia coli 0157 Outbreaks in the United States, 2003-2012.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(8): 1293-1301. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4517704/

- Consumer Reports. “Beef Report.” Consumer Reports, August 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/research/consumer-reports-beef-report/

- USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. “Pathogen Reduction – Salmonella and Campylobacter Performance Standards Verification Testing.” United States Department of Agriculture, February 25, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/wcm/connect/b0790997-2e74-48bf-9799-85814bac9ceb/28_IM_PR_Sal_Campy.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- Consumer Reports. “Beef Report.” Consumer Reports, August 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/research/consumer-reports-beef-report/

- Dibner, JJ and Richards, JD. “Antibiotic Growth Promoters in Agriculture: History and Mode of Action.” Poultry Science, 84: 634-643 (2005). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ars.usda.gov/alternativestoantibiotics/PDF/publications/12JJDibner.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. “Guidance for Industry #213 New Animal Drugs and New Animal Drug Combination Products Administered in or on Medicated Feed or Drinking Water of Food-Producing Animals: Recommendations for Drug Sponsors or Voluntarily Aligning Product Use Conditions with GFI #209.” FDA, December 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AnimalVeterinary/GuidanceComplianceEnforcement/GuidanceforIndustry/UCM299624.pdf

- World Health Organization. “Antimicrobial resistance: Key facts.” WHO, February 15, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/

- World Health Organization. “Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014.” WHO, April 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance (AR/AMR): Biggest Threats and Data.” US Department of Health & Human Services, September 10, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest_threats.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fdrugresistance%2Fthreat-report-2013%2Findex.html

- Food and Drug Administration. “2014 Summary Report on Antimicrobials Sold or Distributed for Use in Food-Producing Animals.” US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/AnimalDrugUserFeeActADUFA/UCM476258.pdf

- Hribar, Carrie. “Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities.” CDC, (2010). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/docs/understanding_cafos_nalboh.pdf

- McEachran, Andrew D. et al. “Antibiotics, Bacteria, and Antibiotic Resistance Genes: Aerial Transport from Cattle Feed Yards via Particulate Matter.” Environmental Health Perspectives, April 1, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.1408555

- Ahmad, Aqeel. “Insects in confined swine operations carry a large antibiotic resistant and potentially virulent enterococcal community.” BioMed Central Microbiology, 11:23 (January 26, 2011). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2180-11-23

- Nadimpalli, Maya et al. “Persistence of livestock-associated antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among industrial hog operation workers in North Carolina over 14 days.” Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 72(2). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://oem.bmj.com/content/72/2/90.full#ref-5

- Consumer Reports. “Beef Report.” Consumer Reports, August 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/research/consumer-reports-beef-report/

- Ibid.

- Association of American Feed Control Officials. “Welcome to AAFCO.” AAFCO, August 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.aafco.org

- Jones, Adam. “Tyson Foods Commands 24% of the Beef Market.” Market Realist, December 11, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://marketrealist.com/2014/12/tyson-foods-commands-24-of-the-beef-market/

- Wiles, Tay. “The ‘chickenization’ of beef.” High Country News, December 26, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.hcn.org/issues/48.22/obama-failed-to-protect-small-scale-ranchers-competing-against-big-ag

- Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture. “Back to Grass: The Market Potential for US Grassfed Beef.” Stone Barns Center for Food & Agriculture, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.stonebarnscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Grassfed_Full_v2.pdf

- Mahanta, Siddhartha. “Big Beef.” Washington Monthly, January/February 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/janfeb-2014/big-beef/

- USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. “USDA Amends Country of Origin Labeling Requirements, Final Rule Repeals Beef and Pork Requirements.” United States Department of Agriculture, February 29, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.ams.usda.gov/press-release/usda-amends-country-origin-labeling-requirements-final-rule-repeals-beef-and-pork

- Code of Federal Regulations. “7 CFR Port 205 – NATIONAL ORGANIC PROGRAM.” Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute, December 21, 2000. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/7/part-205

- Rodale Institute. “Regenerative Organic Certified.” Rodale Institute, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://rodaleinstitute.org/regenerativeorganic/

- Franzlueberrs, Alan. “Cattle Pastures May Improve Soil Quality.” USDA AgResearch Magazine. March 2011. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://agresearchmag.ars.usda.gov/2011/mar/soil/

- Silveira, Maria et al. “Carbon Sequestration in Grazing Land Ecosystems.” University of Florida IFAS Extension, (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ss574

- Rack, Andrea. “How Safe IS Your Ground Beef?” Consumer Reports, December 21, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2019, from https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/food/how-safe-is-your-ground-beef